Assuming his numbers can be trusted (and that’s a huge assumption), Tim Eyman has apparently turned in enough signatures to qualify Initiative 1033 for the November ballot, his most vindictive, dangerous and mean-spirited initiative yet.

I-1033 is a “TABOR” initiative, one of many, similarly constructed spending-cap measures that have been peddled in the initiative states nationwide, and have been funded by a shadowy network of ultra-wealthy, right-wing extremists. Thus, unlike most of Eyman’s initiatives, don’t be surprised to see a fair amount of out of state money flooding into Washington to fund the “Yes” campaign.

The Washington State Budget and Policy Center has a great analysis of I-1033 and its consequences, and I encourage you to watch their slideshow, but don’t think it an exaggeration to summarize the measure as the end of Washington state government as we know it.

I-1033 caps government spending at the previous year’s spending, plus population growth and inflation, and while that may appear to be a formula for fiscal stability, it is in fact entirely and intentionally the opposite.

As I’ve previously explained, Implicit Price Deflator (IPD) for Personal Consumption Expenditures, the inflation index I-1033 uses, comes nowhere close to measuring the rising costs of providing government services. For example, according to the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis, the cost to consumers of durable goods has plummeted 14 percent since 2000, while the cost of consumer services has risen 29 percent. Over that same period of time the IPD (generally accepted to be the most accurate measure of inflation) has risen 21.6% for Personal Consumption Expenditures as a whole, but over 42% for State and Local Government.

So why has the inflation rate for state and local government services risen at nearly twice the rate as that for consumer expenditures? According to a report compiled by the Washington D.C. based Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, it mostly comes down to productivity:

Proponents of TABOR-type tax and expenditure limits sometimes contend that a growth formula based on population plus inflation would be adequate to maintain public services at a roughly constant level. But researchers long have recognized that the services provided in the public sector, such as education, health care, and law enforcement, tend to rise in cost faster than many other goods and services in the economy in general. This analysis was first put forward by economist William Baumol, who pointed out that technology and productivity gains may make goods cheaper to produce, but the services that government provides are different. Baumol said public services typically rely heavily on well-trained professionals — teachers, police officers, doctors and nurses, and so on — and technology gains do not make these services cheaper to provide. It may take far fewer workers to build an automobile than it did 30 years ago, but it still takes one teacher to lead a classroom of children. (In fact, as education has become increasingly important, the trend is toward more teachers per pupil, not fewer.) Doctors generally still see patients one by one, and nursing care remains labor intensive despite technology.

Even in a stable economy, population plus inflation just can’t keep up with the rising costs of providing government services, resulting in government spending power dropping year after year after year (as is already happening in WA state under our current unfair and inadequate tax system these past fifteen years). But of course, our economy is not stable, and here is where I-1033’s true destructiveness comes into play.

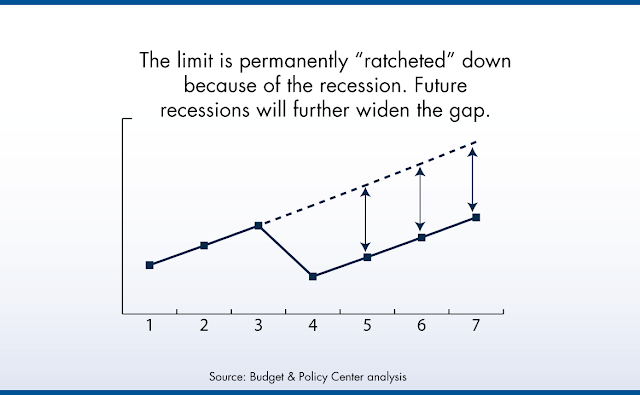

I-1033 would limit annual spending to that of the previous year adjusted for population growth plus IPD, which means that during every economic downturn, the base level of spending from which future increases are calculated will be ratcheted down to the lowest revenue point, creating an ever widening gap between projected spending increases, and those actually allowed under I-1033.

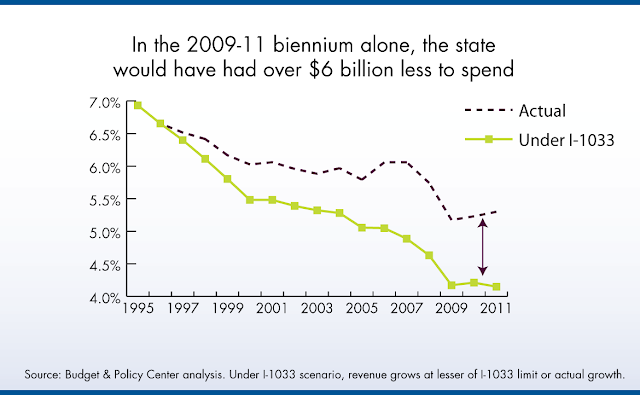

Of course, Eyman chooses the trough of our worst economy since the Great Depression on which to base future revenue increases, but even if he hadn’t, the inevitable result would still be a dramatically smaller government, and in short time. For example, had I-1033 been implemented in 1995, revenues during our current, already squeezed biennium, would have been $6 billion lower than they are now.

How much is $6 billion? That’s the current state budget for higher education, natural resources, public health, early learning, corrections and the Basic Health plan… combined!

Like I said, it’s not an exaggeration to describe I-1033 as the end of state government as we know it. In fact, the consequences would be so unbelievably dramatic that there is almost a sense of complacency amongst the opposition—we simply can’t believe that the majority of voters could be so stupid as to pass such an incredibly irresponsible measure.

But it’s ignorance, not stupidity that frightens me.

If I-1033 draws in national money from the usual pro-TABOR suspects, this could be an awfully tough fight. The TABOR camp has spent years honing their rhetoric and talking points, and Eyman has been dutifully aping their instructions since filing. It’s going to take a lot of voter education to defeat this measure, and with the weakened state of our local media, and the generally timid demeanor of our political leaders, I’m not entirely confident that we’re properly prepared to defend against this latest assault on our quality of life.